The Art Museum of Reykjanesbær begins the year 2019 with a solo exhibit of works by the artist Guðjón Ketilsson. The exhibition is titled “Teikn”, meaning symbol, omen or sign, and consists of eight different works which all have aspects of symbols, symbolism or the “reading” in the most general sense. The artist has put equal effort and thought into works in three-dimensional space and on two-dimensional paper. The work is at the same time a master craft and contemplation on the existence of man, the mark he makes on reality with his actions and the methods he employs to be understood in his own cultural community. Many of Guðjón’s greatest works are full of allusions, symbols and references that form a kind of subjective space that the viewer becomes a participant in and experiences in a very physical sense. It is this kind of work that makes up the exhibit “Teikn”.

Guðjón is among the nation’s most significant visual artists and has had over thirty solo exhibitions and taken part in collaborations around the world. He has received many recognitions and his works are on open display in various locations. For example, he participated in the collaborative exhibitions “Þríviður” in the Reykjanesbær Art Museum in 2008, which the media considered one of the best displays of the year. Guðjón’s work can be found in all main art museums of the country. We are both delighted and honored to have him here with us again in Reykjanesbær and wish to thank him for his collaboration with us. The exhibits curator is Aðalsteinn Ingólfsson, art historian, and along with him the poet Sjón writes an introductory contemplation about the “found hieroglyphs” of Guðjóns work in the exhibition catalogue and examines their conceptual message. We thank them both for their contributions.

Signals

“Space has values peculiar to itself, just as sounds and scents have their colours and feelings their weight.” Claude Levi-Strauss – Tristes Tropiques, trs. John Russell.

With the exception of the dissolution of the solid mass, probably the greatest and widest-ranging influence upon three-dimensional art in recent decades has been the activation of subjective space – which is one of the more interesting long-term consequences of conceptual art. Hence the focus has shifted from significant objects – made or created by the artist or nominated by them (see Duchamp) – to the space in which the object exists. Thus the space is transformed into something like a stage set – which does not diminish the significance and impact of the object per se, as was often the case during the heyday of minimalism, but establishes an emotional magnetic field around it, rich in complex overtones. The object itself, at the heart of the work – or the

cluster of objects in the case of an installation – is not in the nature of an autonomous whole, or a final conclusion: it is more of a guide, an enigmatic clue cast into the void in the direction of the observer.

As an artist, Guðjón Ketilsson has been so thoroughly identified with materiality – and especially the diverse natures of wood – that less attention has been paid to the skilful way in which he establishes a subjective space for his works. The foundation of that space is laid, largely at least, through pure and simple craftsmanship: the meticulous arrangement or working of tree trunks, wooden blocks and sticks, their formation and finally the refinement of the finish. To Guðjón, craftsmanship is a necessity; he has likened it to archaeological excavation – the removal of layers, one by one, until what is left is some significant clue – presumably to the nature, adaptability and “concealed“ meaning of the material with which he is working. Also applicable here is the philosopher Theodor Adorno’s remark about good craftsmanship: while it is a prerequisite for a good work of art, it never draws attention to itself. Instead it allows the work to become something beyond itself.

Guðjón’s works may thus be termed, unapologetically, both masterpieces of craftsmanship and contemplations of human existence – the footprints humans leave in the real world by their deeds and the methods they apply in seeking to be understood in their cultural context. In almost every case we are faced with works which do not encompass their complete significance – which is in principal what a painting does – but are bursting with clues, symbols and references – signals – which establish a space which we enter and experience gradually, for ourselves. In Guðjón’s art that space is mainly of two kinds: on the one hand works that are grounded in the absence of objects; on the other in their proximity. The former approach is exemplified in his series of woodcarvings (2000) based on a renowned 16th-century painting by Peter Breughel the elder, The Peasant Wedding. Guðjón makes copies of the headgear of all the figures in the painting and arranges them on a wall, reflecting their placement in the painting. The absent figures here lead us to consider what is missing – the body (our own and others’) and how it responds to social and religious circumstances at different times: in this case the class divisions reflected in the different kinds of headgear in Breughel’s work. Ultimately, the work raises questions about our ownership of the body: whether it belongs to us at all, or whether we simply borrow it momentarily – like a hat or a cap.

Some of Guðjón’s other works, such as Surface/Structures (2011), owe their dynamic to an abundance of objects, not their absence. In that work – an assemblage of wooden boxes and found cupboards of blond wood – a bizarre space is created in which the macro-space of building and the micro-space of various furnishings and cupboards intersect, and each space within the whole has its own story and time. Every unit is both like the rest, and unlike them; and this friction between the known and the unknown disrupts the norms and consciousness of the observer, establishing tension between him/her and the work.

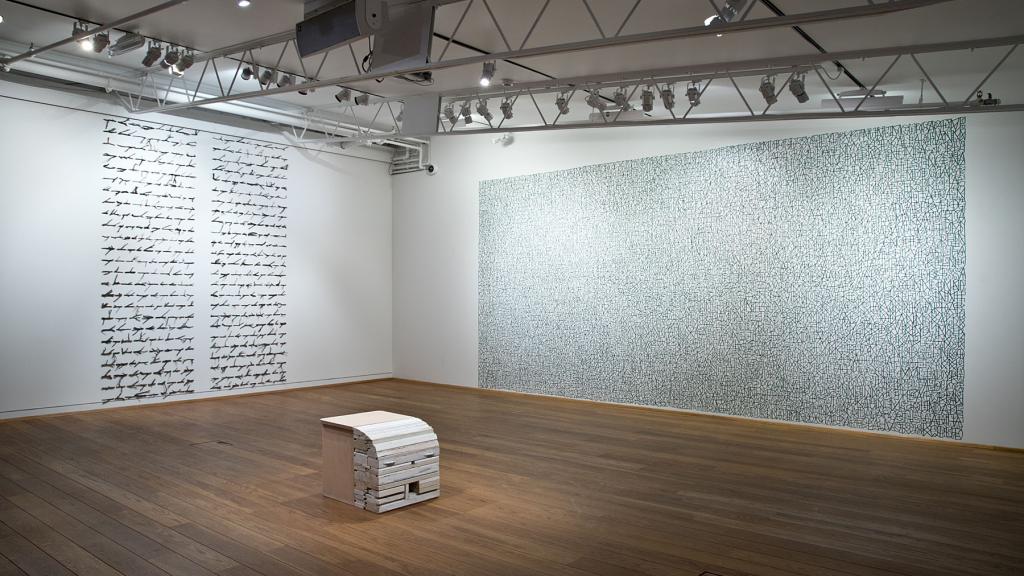

In the Reykjanes Art Museum gallery Guðjón is now presenting an overview, though not a conventional “retrospective.” The exhibition is unusual in that the artist has not chosen to sum up his whole career, opting instead to link together a number of “drawings” on walls and floor pieces made in recent years. The link underlines the ideological connection in Guðjón’s art between drawings, reliefs and three-dimensional works, as the observer is drawn into a world based on written symbols, their significance and cultural dynamism. And if that sounds like a scholarly summary, it is impossible to overstate how rich, unpredictable and poetic that visual world is when one enters it.

The two-part division of the show is almost a given: the drawings are displayed along the length of the walls, while the three-dimensional pieces are displayed along the length of the gallery.

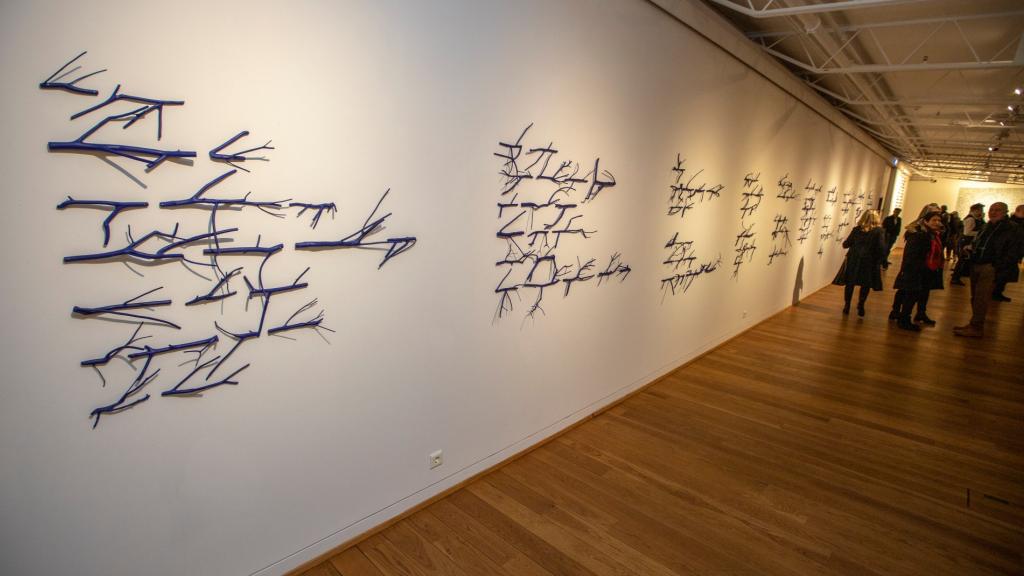

The former group themselves into graphic clusters which remind us how dependent both writing and drawing are on space and “chance” – no less than three-dimensional pieces. In the open space of the gallery they are without beginning or end: limitless. With a certain poetic licence it may be maintained that the wall pieces present an impression of the evolution of written symbols – although that may not have been Guðjón’s intention. The major element of the show comprises “natural lettering” – random messages from nature in the form of twigs cut by the artist in his garden. The artist has painted the “messages” with blue ink and arranged them like stanzas of verse. But the stanzas entail no narrative or progression; they are what Barthes called “writing degree zero.”

At the next stage, the mural drawing on the subject of the Creation, we are faced with writing/drawing as pure progression, yet with existential overtones.

Guðjón writes along the wall, in fits and starts, the story of the Creation as told in the first chapter of Genesis, which is one of the fundamental pillars of Christian history and western civilisation. But here the writing of the text is grounded in a new formal and graphic language that entails deconstruction of the text, and at the same time visual innovation. Creation and destruction are indissolubly linked, and the circle of life goes on.

Guðjón’s Hymns of the Passion is displayed on the end wall opposite the Creation, and the two works interact in a variety of ways. Both are drawn essentially using the same method, constructing and simultaneously deconstructing. Hymns of the Passion was made in Rome, the heart of Christianity and the baroque, during Lent in 2016. Guðjón set out to honour Iceland’s foremost devotional poet, the 17th-century cleric Hallgrímur Pétursson, whom he calls “the embodiment of the Icelandic baroque style,” by penning each of his fifty Hymns of the Passion on a small sheet of paper (17 x 24 cm), until all had been written. Guðjón’s original idea was conceptual in nature: he intended to complete the ambitious piece within the forty days of Lent. In the event the work was 19 months in the making: the artist wrote out hymn number 50 on Good Friday (30 March) 2018. Here it is the quantity of text crammed onto each sheet that transforms each hymn into a near-illegible graphic mass – i.e. the text becomes an image. The fifty hymns are here framed and linked together. The artist plans to publish them in book form, which will undeniably be a new stage in the evolution of the work: text becomes image, and that in turn becomes a book.

In both works Guðjón addresses the question of whether the content of these texts is permanently lost by their deconstruction, or whether their resonance or “aura” persists despite the change of form.

As for Guðjón’s floor constructions, they are the dwelling-places of literary art in the real world. These have started their lives as recycled cupboards, chests of drawers and cabinets, which the artist has sanded down, removing all ornament, handles and other inessentials. The freestanding units which are left contain or surround three-dimensional units of writing or symbols, which their nature are linked with the text masses referred to earlier: piles of books comprising volumes which have been stripped of their external features. And again one may ask: are these stacked books still “readable” in any sense, or does their “book meaning” coalesce with the formalism/architecture of the containing units, thus establishing new norms?

In these works, as in so much of his art, Guðjón constantly explores new means of re-evaluating the relationship between environment and culture.

Aðalsteinn Ingólfsson

Translation: Anna Yates

FIVE TRANSLATIONS FROM THE LITERATURE OF TREES

When I accepted the invitation to decipher Guðjón Ketilsson’s tree pictures, I had no idea how difficult this would turn out to be in practice. On the contrary, I felt sure of my qualifications for the job, having been immediately struck by the works’ resemblance to the type of human creativity known as poetry: rows of longer or shorter words, laid out in lines of varying lengths, coming together to form individual stanzas of varying size, themselves often grouped with other stanzas of varying number. And since I have spent the last forty years engaging with poems as a reader, poet and translator, I embarked on the exercise full of a misplaced confidence.

The first aspect I had to stop and consider was how much effort had already been put into teasing out the meaning of the works before I got to see them. The artist’s choice of twigs, his decisions about which way round to place them, how to combine them, how many to include on each line and in the artwork as a whole, the colour he painted them – all these factors channelled the interpretation in a particular direction, which inevitably set limits for me. But since Guðjón has had a longer, more intimate relationship with wood than almost any of our contemporaries, I concluded that I should trust implicitly in his preparatory work with his materials.

Another aspect that gave me pause was the way the mounting of the twigs on a white background precluded a fully three-dimensional view of the ‘words’ – which, on closer inspection, could be individual letters or whole sentences, paragraphs or even chapters, hieroglyphs or a form of sign language – but this was compensated for by the shadows they cast, which I chose to see as enhancing or emphasising the meaning. I wonder, though, if a text of this kind can ever be fully understood (one can but dream) except by running one’s fingers over it.

My original optimism might have been due to the blueness of the ‘words’, evoking, as it did, the blue ink of the fountain pen I wrote with as a child at school. The memory was curiously soothing, though my relationship with the pen was sometimes fraught – I can’t think of it now without the tip of my index finger and the edge of my hand turning blue in sympathy – and I looked forward to whiling away a pleasant December afternoon on a satisfyingly challenging yet leisurely dialogue with the five ‘poems’ the artist had chosen for me from his collection.

For the translations themselves, there was little help available: no dictionaries, in Icelandic or any other language – a problem faced by every pioneer – and without the inspiration provided by Dr Alexander Jóhannesson’s etymology or Professor Finnur Magnússon’s work on the rune-like inscriptions at Runamo, I would probably have given up in despair. In the end, the ‘poems’ proved to be a far more complex and varied ‘literature’ than I had anticipated, and the task of translation became ever more arduous as my knowledge of the language improved. This quality, at least, it shared with other types of writing.

I suppose I had been expecting something lyrical, like the nature poetry of the Japanese school, something limpid and grateful. But there I underestimated the trees – and their intimate friend, Guðjón Ketilsson.

A)

head divided from trunk

the dead come to no one’s aid

a trunk halved, a rooted horizon, a child

where once we lived little grows out of much, our children sleep in the soil

an unexpected guest appears, puts down roots

a westerly wind, layers of earth stripped bare, days of hardship

trunk seeks new head

B)

(a round)

go on! swim

swim sisters – swim along the shore

along the shore!

go back! go back unconquered

sing sisters

go on! swim – go back / to you

C)

Read from the bottom, from right to left. Together the ‘letters’

form a noun in the feminine singular: ‘mechanical bride’.

D)

life – an ice-sheet

weeping and splitting

orchards – clouds

from sea to sky

follow me up above the clouds

the sun burns in the depths

E)

This is an introduction to a work on ornithology from the trees’ perspective. The introduction fills three volumes; the study itself is said to be much longer, taking up many metres of shelving, in human-book terms. There is no room here for more than a brief synopsis. The first volume relates how the trees created the birds after they themselves had come into existence during a lightning storm. The second volume traces the history of ornithology among trees and describes the main works that paved the way for the present one. The third volume discusses the origins of the work and its authors. Their innovative classification system seems to have met with hostility from older scholars. Prejudice against certain species of birds is a frequent feature.

Sjón

Translated by Victoria Cribb